Cosa facciamo

Diamo forma a una nuova generazione di servizi ed esperienze, sistemi e piattaforme in contesti sempre più ibridi, tra fisico e digitale.

Scopri di più

Abilitiamo, coinvolgiamo e formiamo le persone, le comunità e le reti, per adottare nuovi comportamenti e agire in un contesto in continua evoluzione.

Scopri di più

Sviluppiamo, alimentiamo e ci prendiamo cura di community, dentro e fuori le organizzazioni.

Scopri di più

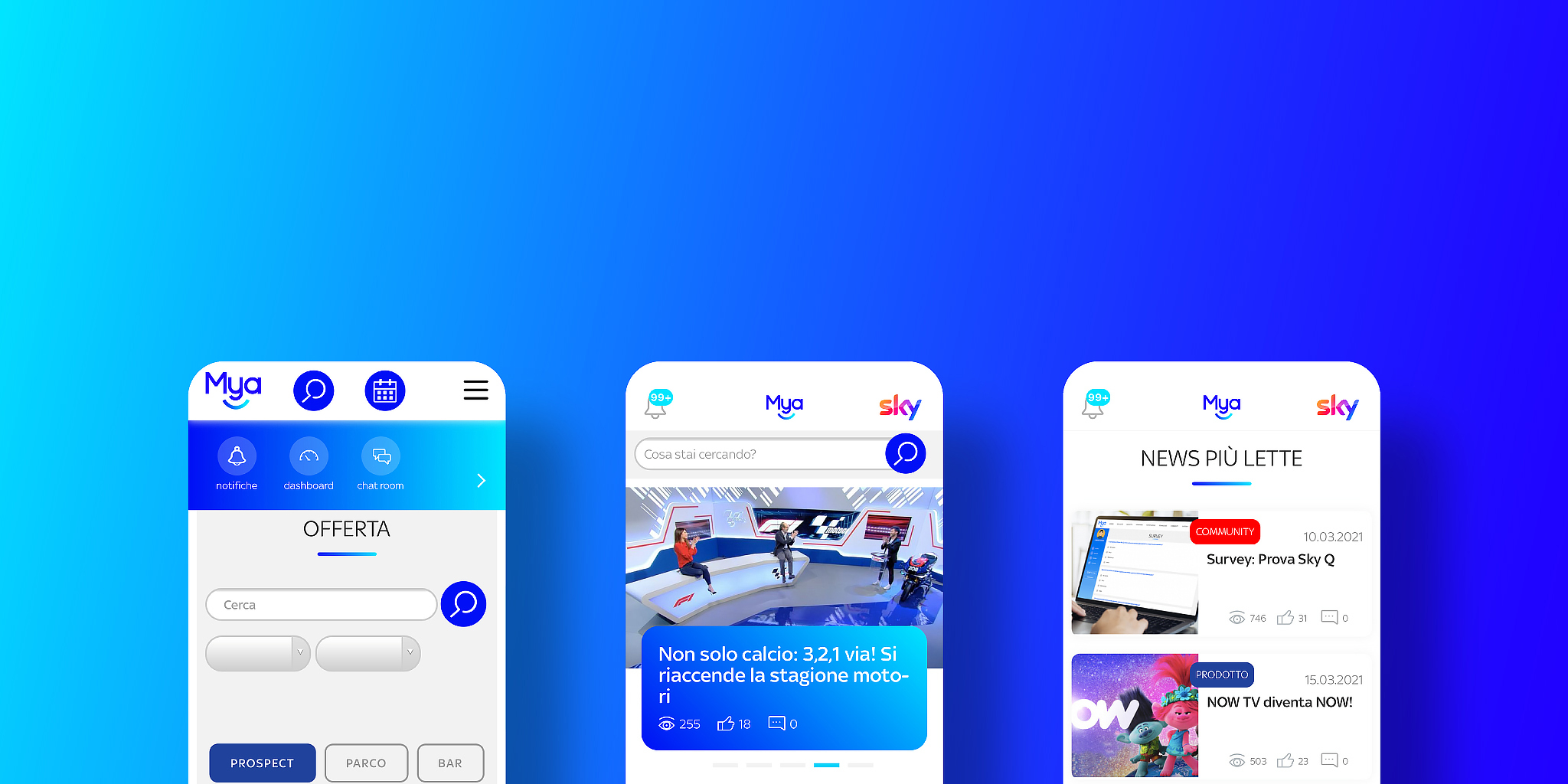

Sviluppiamo piattaforme e strumenti digitali con tecnologie proprietarie oppure implementando soluzioni di terze parti.

Scopri di più

Realizziamo progetti di ricerca e sperimentiamo approcci alternativi.

Scopri di piùImpact design, il nostro metodo progettuale

Crediamo nel design che mette al centro non solo le persone ma anche le comunità – People & Community driven. Interpretiamo i loro bisogni, progettando per loro nuove azioni, esperienze, storie. Questo è il nostro perimetro di azione. L’Impact design ci permette di abilitare persone, organizzazioni, ecosistemi all’innovazione e a comportamenti nuovi, entrando nel merito di ciò che le motiva, allenando nuove sensibilità e nuovi spazi interpretativi. L’Impact design ci consente di generare impatti positivi e ottenere risultati concreti e misurabili.

L’Impact design è sistemico e multidisciplinare.

L’impact design è sostenibile e inclusivo.

L’impact design è collaborativo e partecipativo.

L’impact design è bellezza.

Magazine

Insight, ricerche, osservazioni e riflessioni sulle grandi e piccole trasformazioni in cui siamo immersi. Una lente per comprendere sfide, opportunità e impatti per persone, organizzazioni e società.